Your riparian fencing can perform many functions.

As well as keeping stock out of your riparian area, your fenceline could:

- support a new paddock subdivision that will help you graze your land more effectively

- form part of a laneway for easier stock movement

- provide opportunities to alter your paddock layout to take advantage of future shade and shelter

Where and how you build you fence will be influenced by factors including the type of waterway, terrain, cost, proximity to power and existing infrastructure, flood risk and the way you intend to use your riparian land.

The photos, diagrams and information in this section will assist you in your decision-making process.

Fencing to control stock access to your riparian area is a key management strategy that – with good planning – will enable you to achieve multiple environmental and productivity objectives.

Fence to create a functional riparian buffer zone

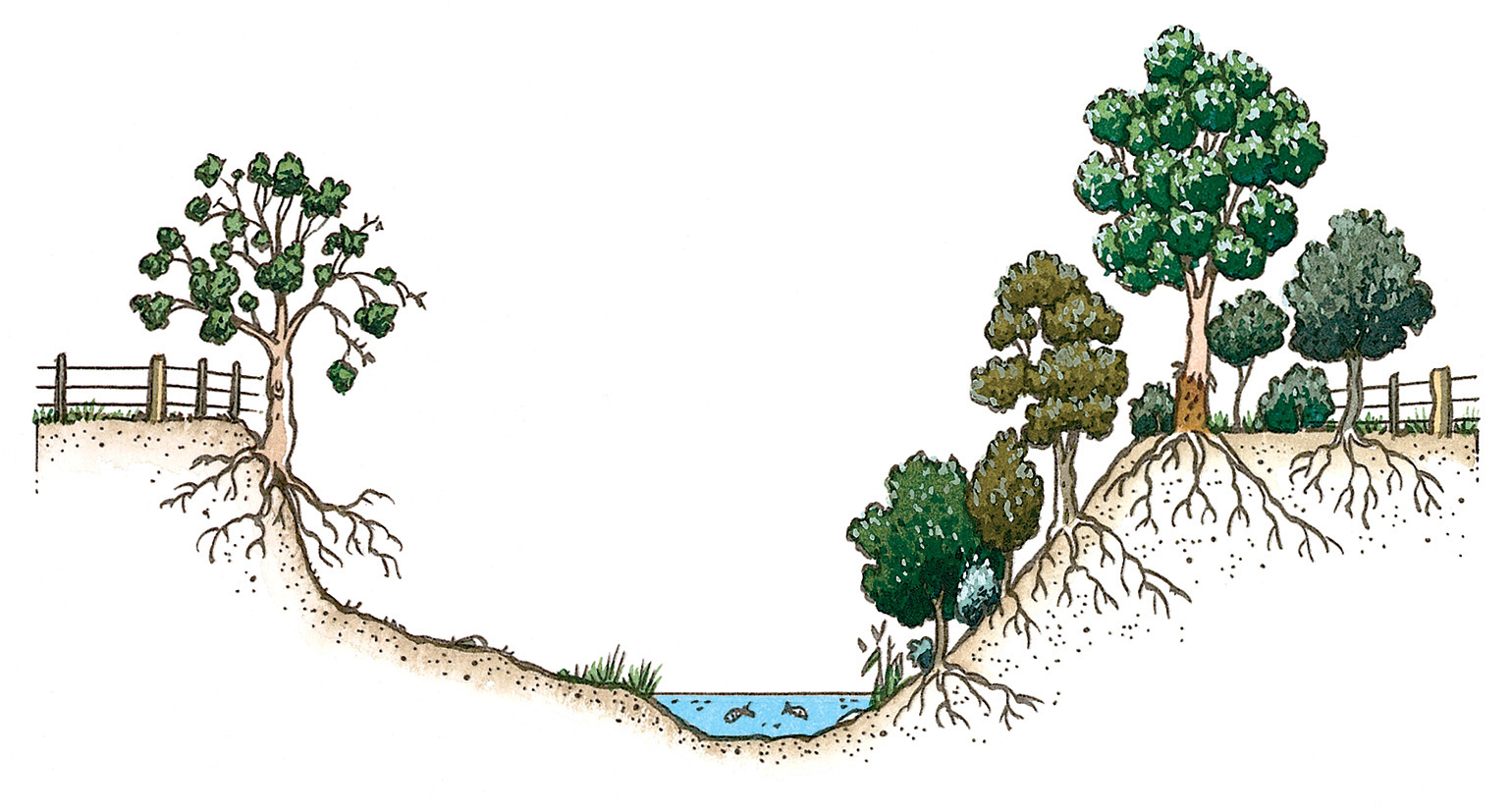

Ideally, the riparian buffer will include all your riparian land, the size of which will vary according to the type and size of your waterway (see How much riparian land is on my property? in Section 1).

If fencing off all your riparian land is not possible, prioritise the immediate riparian zone (often called the fringe or channel corridor), that runs next to the waterway.

The immediate riparian zone is often characterised by a relatively steep slope and – in healthier riparian areas – denser vegetation. If vegetation cover is poor, this area will be prone to erosion and instability, and soil and nutrient run-off will be excessive.

The edge of your riparian land is usually indicated by a change in land type, vegetation and/or soil type. These changes are often visible in a satellite image or aerial photo, as well as survey and topographical maps.

Fencing a waterway with a gentle slope.

Fencing a waterway with a steep slope.

Fencing a waterway with a floodplain.

Don’t skimp on your setback

You should build your fence as far from the waterway as possible. As a general rule, allow a setback of at least 10m from the banks of a small waterway and 20m from the banks of a large waterway.

Be prepared to allow a deeper setback if:

- you have active erosion, unstable banks, scalding or other signs of degradation.

- your riparian area is in poor condition (see Assessing the health of your riparian land in Section 10).

- you want to create habitat for wildlife. In this case, allow a setback of at least 30m to create an adequate corridor, and protect as many existing shrubs and trees as possible.

Most funding bodies impose minimum setbacks (and other conditions) as part of their funding agreements, so be sure to ask lots of questions and arrive at a decision that meets both your and the funding agency’s needs.

Use changes in land type to guide you

The ideal place to build your fence is often where there is a change of land type or natural landform, such as a ridge.

Whether you follow the exact contours of your waterway, however, may be determined by cost. Straight fences are cheaper and simpler to erect than fences that follow the bends and curves of the waterway because there are less end assemblies involved. The risk of flood damage is also reduced as debris can’t become caught in the bends of the fence.

Avoid building on or near the top of an embankment as this will cause instability.

Straight fences set back some distance from the waterway are a good option if your waterway is dynamic (changing course) or if erosion is a problem.

Choose the location of your gates carefully

Poorly sited gateways can create run-off problems, especially if they are used regularly by stock and/or vehicles. Aim to build your gateways:

- as far from the waterway as possible.

- on high, stable ground with no signs of degradation.

Drop-down or lay-down fencing and electric bungee cords are cheap alternatives to gates, especially in flood prone areas.

Make sure you leave good access for vehicles and any machinery or equipment you may need to manage your riparian area.

Controlling animals other than stock

Riparian areas, whether fenced or not, are used by many types of animals to travel across the landscape. As your waterway becomes healthier, this traffic is likely to increase.

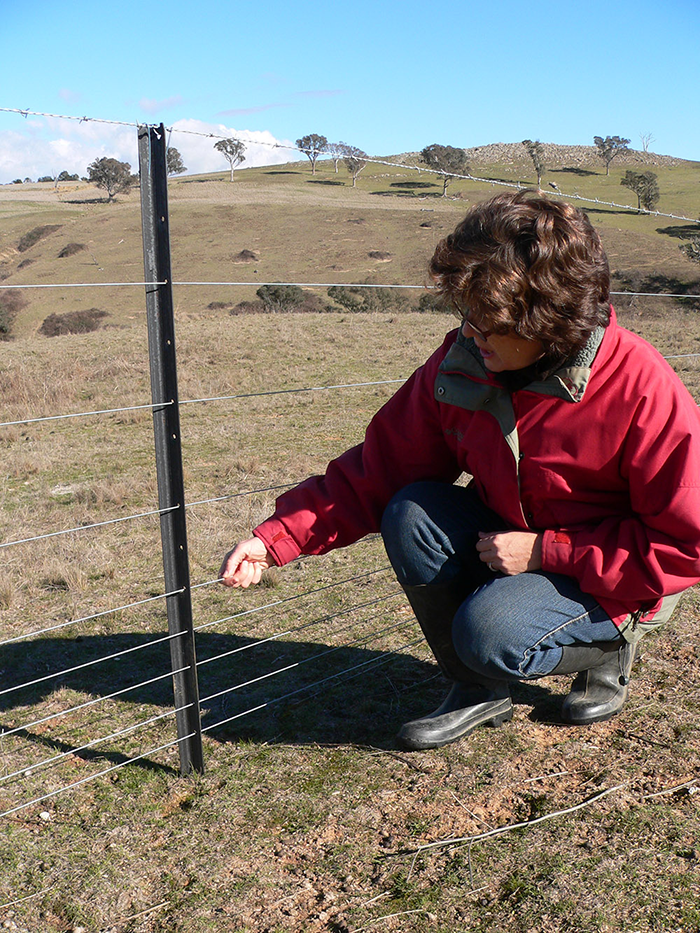

When planning your fencing, consider what animals, other than stock, you may need to manage. There are several different kinds of prefabricated fencing and electric fencing techniques available that may be useful. If you need to fence across your waterway to prevent unwanted animals entering your property, the information below will assist you.

Important Note: Fencing across navigable waterways is illegal. Navigable waters means all waters (whether or not in the State) that are from time to time capable of navigation and are open to or used by the public for navigation, whether on payment of a fee or otherwise. Please ensure you check the rules and legislation within your jurisdiction before fencing across any waterway.

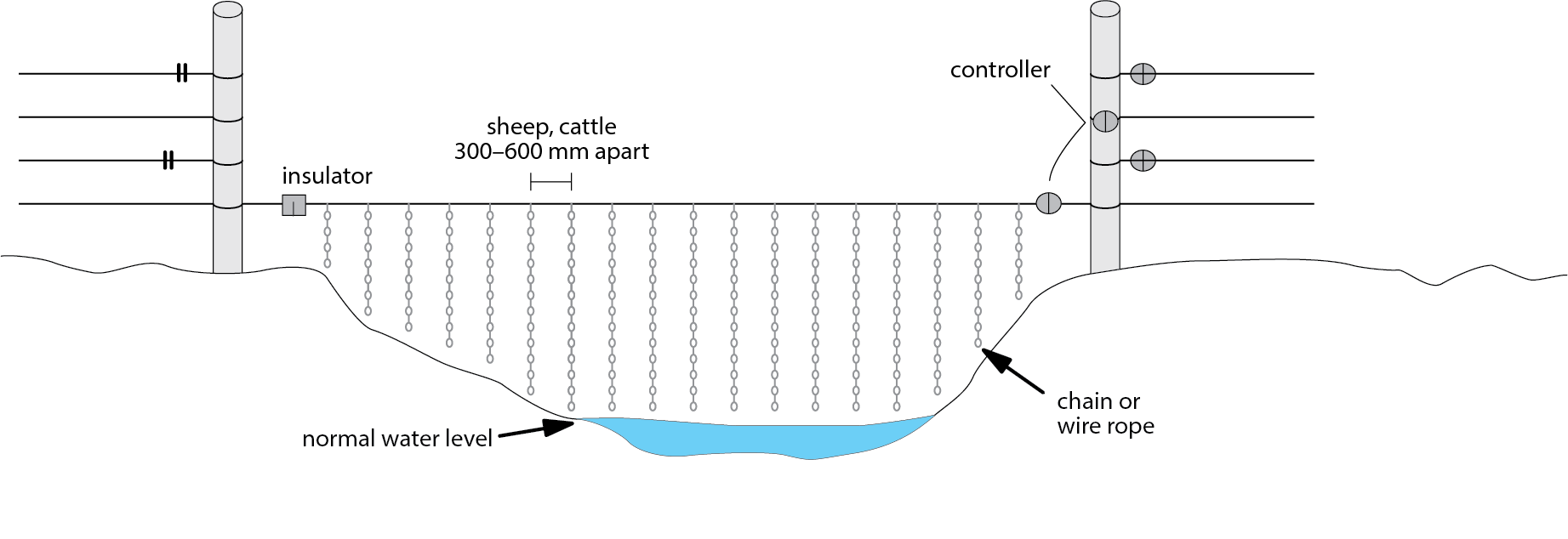

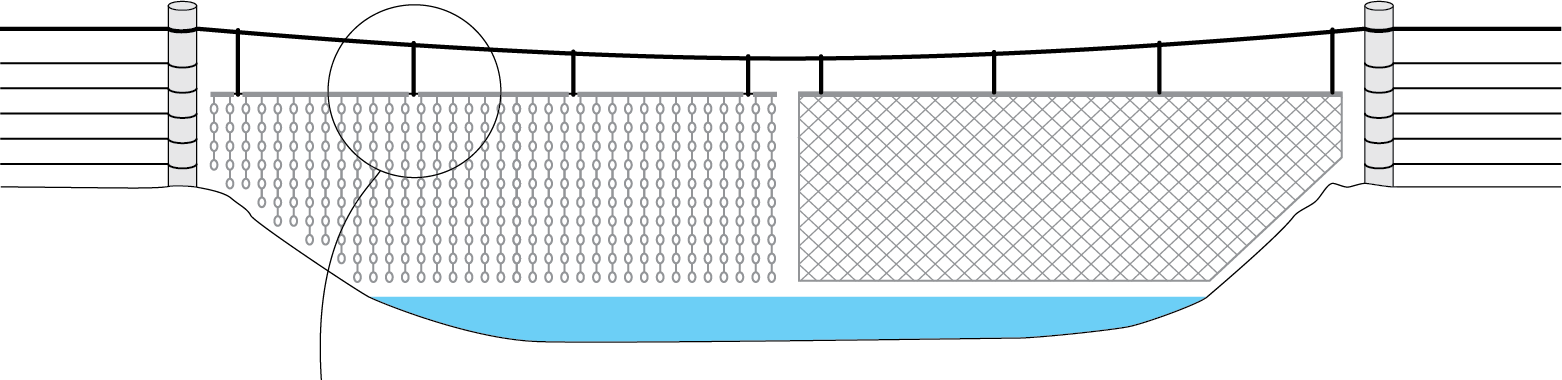

There are several options for fencing across a waterway ranging from the very simple (one or more electric wires) to the more sophisticated (suspended fences and hinged floodgates). The choice will depend on many factors including the potential for flooding, the type of stock you run, the need to exclude pest animals, the likely amount of stock pressure on the fence, and cost.

Plain wire electric fencing is often a good option because it requires less structure than other types of fencing. If vertical support is required, steel pickets can be inserted in the bed more easily, and with less risk of erosion or damage to the banks and/or riverbed than ordinary posts. Avoid using mesh which will collect debris and put pressure on the rest of the fence.

Make sure any fencing that crosses a waterway is built independently of the rest of your riparian fencing.

This will reduce the risk of damage to your entire fenceline if the waterway floods.

Fencing across a waterway

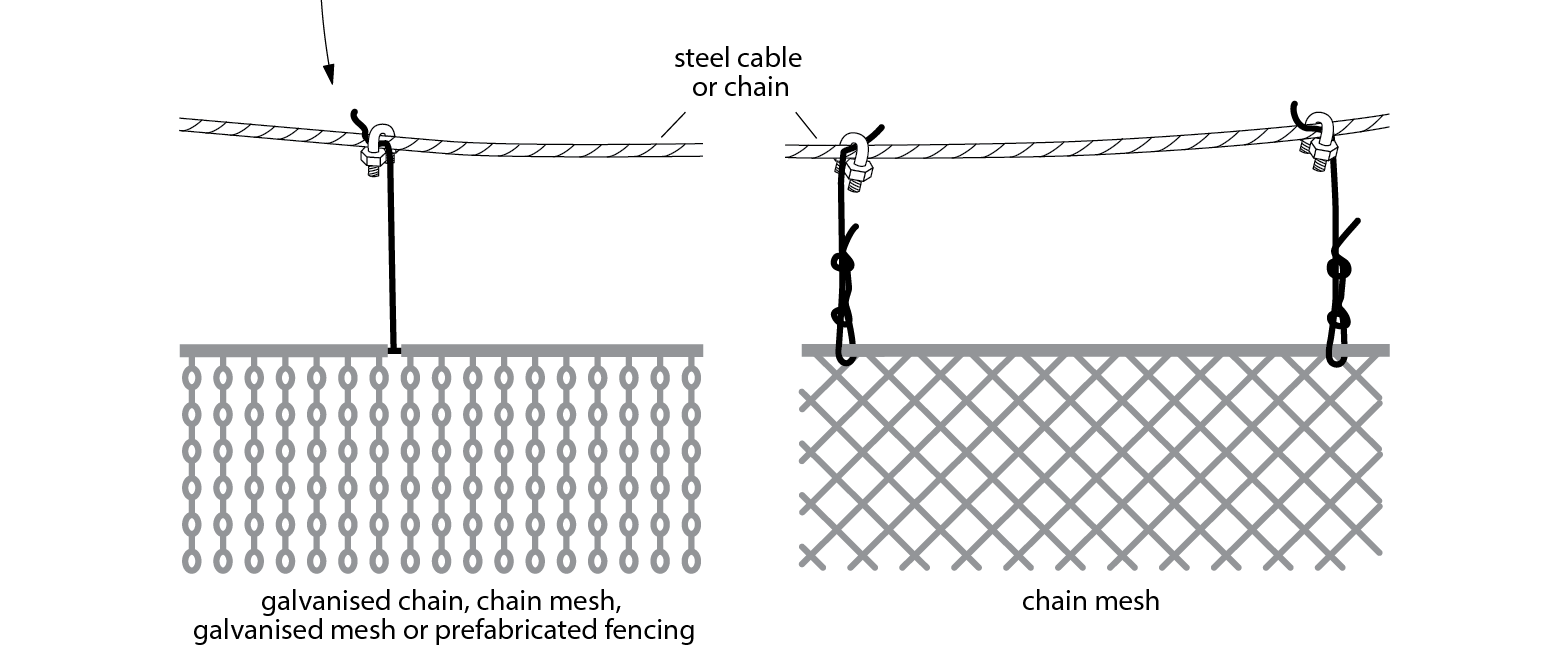

Electrified suspended or hanging fence made of chains. Suitable for waterways that flood.

Suspended cable fence made with chains of left and mesh on right.

Detail of cable fence described above.

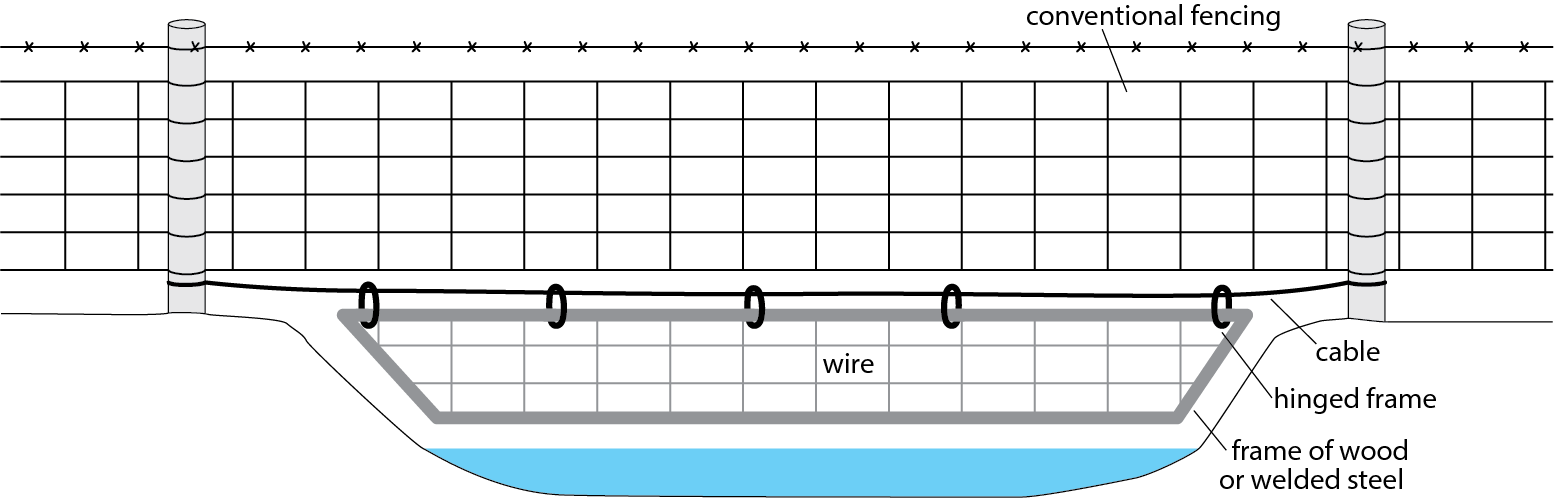

Hinged floodgate.

All diagrams provided by Allison Mortlock.

Tips for building flood-resistant fencing

Extreme weather events are becoming more frequent. Heavy rain combined with a lack of vegetation cover across the landscape often results in flooding, leading to the loss of fencing and other farm infrastructure.

While it will probably never be possible to design a fence that will withstand the force of a major flood, you can reduce the risk of flood damage by:

- building your fence as far above the flood line as possible.

- building parallel to the likely direction of the flood flow.

- not building your fence across the waterway.

- having as few curves or corners as possible (to avoid creating pockets where debris can collect and put pressure on your fence).

- using plain wire in preference to prefabricated mesh or barbed wire which are more likely to collect debris and put pressure on your fence.

- keeping the number of wires to a minimum (to avoid collecting debris).

- avoiding using droppers (to avoid collecting debris).

- using thicker and/or deeper posts, especially in sandy soils.

- driving in your posts rather than back-filling or in-filling the hole.

- reinforcing your end assemblies.

- reducing the space between your fence posts.

- keeping fences to a minimum height (as fences lose stability with height).

- maintain wire tension to promote wire vibration which will help minimise debris loads.

- using anti-sink and anti-lift devices on crests and in depressions.

- building your riparian fencing (and/or high-risk sections) independently of your main fenceline.

If the risk of flood is high, consider using using drop-down or lay-down fencing for all or part of your riparian fencing (see photo below).

Many farmers in floodprone areas incorporate sacrificial wires in their fencing that they are prepared to lose or cut in order to protect the main fenceline.

Drop-down fencing folds down automatically in response to the build-up of pressure and allows water and debris to flow over the top of it. In contrast, lay-down fencing needs to be released manually. Both are easily re-erected after the flood.

PUTTING IT INTO PRACTICE: GARRY’S STORY

A 200m setback sounds like a big sacrifice, but for Garry Kadwell, fencing off his entire floodplain was a sound business decision.

Garry, who runs a mixed farming enterprise in Crookwell, appreciates the important roles a healthy floodplain plays in improving water quality, and providing shelter for stock and habitat for wildlife. He also knew from previous experience that dedicating land to conservation would actually lift overall farm productivity rather than take away from it.

“The floodplain is my farm’s agricultural filter.”

A fourth generation farmer, Garry is a Landcare champion, and well-known for his work both in the local community and agriculture.

He brought 196 acres of “clapped-out, weed-covered land” adjoining his original holding at the head of the Crookwell River in 2011. Although it hadn’t been stocked for 15 years, historical overgrazing had left its mark.

“It was overgrown with blackberry and phalaris,” he recalls. “There was a scattered handful of Eucalyptus stellata trees but even they were in bad shape.”

What concerned him the most, however, was seeing the river “run red” with huge loads of basalt soil after heavy rain.

While many people would have opted to fence off just the immediate riparian zone, Garry – who grows seed potatoes, runs prime lambs and produces fodder – decided to fence off the entire floodplain.

Working from a whole farm plan, he set about establishing a new dam and watering system, and creating a number of smaller paddocks that have been improved with species including lucerne and Sudan grass.

Garry, who has a Certificate in Conservation Earthworks, carried out a number of projects designed to slow the flow of water across the landscape and create a mini-wetland. He also scalped back some extremely degraded areas to give seeds from nearby mature trees the chance to naturally regenerate, and hand-sprayed the blackberry.

The area transformed itself very quickly. “Water quality improved within 12 months, the total ecology changed within five years, and there has been so much regrowth that we can expect full shade and shelter within ten years,” says Garry.

He has no regrets at the loss of grazing land, saying that locking up the floodplain has actually boosted overall production.

“The floodplain creates shelter from wind and reduces evaporation leading to better pasture, stock and crop growth,” says Garry. “I’ve also gone away from pesticides thanks to the beneficial insects and birdlife that help combat potato pests like aphids and grasshoppers.”

Gary regards the improvement in water quality, however, as his biggest achievement. “The river always runs clear whenever it leaves our place after rain,” says Garry, proudly.

Download a PDF copy of Section 5: Riparian Fencing.

Fill in the form below and we’ll send you a digital copy.

We have incentives available for managing stock around waterways on your farm…

Through our Rivers of Carbon program we can help you manage stock around waterways. We will visit your property and work with you to develop a plan for your waterway that may involve fencing, off-stream water, small-scale erosion works, and re-vegetation.

Once we have an agreement in place on what we want to achieve together, we generally cover at least half of the costs involved in implementing the agreement. Click the button below to learn more about our program:

This website is a collaborative project between: